I shall hold you close

If I seem distracted at all

It’s merely soft winds of the sea

The sight of islands off the coast

— Ben Howard, Lotus flower

The Atlantic Ocean is wild today. The upper deck heaves dangerously over the waves. Behind us a trail of foam as white as the hills of Knoydart on the horizon. We're alone on this ship, us and a handful of others. None of them with a rucksack like ours. Winter is nearing, and we’re heading straight for the snowcapped peaks jutting out across the sea. The peaks of the Rùm Cuillin.

The island Rùm, one of the Small Isles, is one of the wildest islands in the Hebrides. For its modest size of 8 by 8.5 miles it is incredibly mountainous: the ascent of its Cuillin range – the highest peak 812 m – rivals its namesake on Skye. The 30 or so residents of Rùm all live in the bay of Kinloch. On the rest of the island red deer reign.

Upon docking at the pier, the other passengers go straight into houses along the bay. On the darkest days of the year, Liam and I are the only visitors here. No wonder – Rùm is a wretched cold place in winter. And yet my mind wanders back here year after year. To those days in the dead of December, when I didn’t see the sun for days. I have a strange longing inside me for misery.

Guirdil

We spend the first nights on Rùm in Guirdil, a secluded bay on the west coast of the island. Here lies a bothy, tucked breathtakingly below steep hills.

The way there is a long trudge, first extremely slippery with glaze (our crampons are greatly missed), later drenched in bog. But the views are brilliant, to Skye in the north and the Rùm Cuillin in a white cloak. The snow line is clearly visible, at about 300 m altitude currently. Between us two we drag more than 40 kilos over the mires and rivers. By 4 p.m. the sun has set behind Bloodstone Hill (388 m), the spectacular hill above the bay. In the twilight we descend to Guirdil Bothy. A bachelor herd of stags lets us come near before it gallops away. They make it clear: this is their territory.

Those days spent in Guirdil, our world narrows to the gable roof and the coves around the shore. Rain and wind lock us in, and soon not even Bloodstone Hill’s flat summit can be seen. Our only reminder of a world outside this godforsaken bay is the sight of the Isle of Canna off the coast.

Guirdil is a place of reflections and murmerations. Waves fill the corners of my mind. At night I read for hours by the hearth, and enter a world of sailors and mythical creatures. In one sitting I finish The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway. With the sea roaring outside it isn’t hard to be immersed in the story of the old man fighting a giant marlin.

Liam spends his time splintering wood for the fire. Wet logs steam on the cold stones. That’s how we get through the long hours of the evening, in that small circle around the fireplace. Outside of it, it’s only a couple degrees above zero.

He rested sitting on the un-stepped mast and sail and tried not to think but only to endure.

Later that night, wind pounds on the skylight above the loft where we sleep. From the southeast it has free rein through Glen Guirdil. During the day we wanted to climb Bloodstone Hill, but at sight of the low clouds and rain we decide against it.

We still go out, because there’s lots to explore here, even on a rainy day. Bloodstone Hill is named after bloodstone, a shiny green mineral speckled with red; around the British Isles it can only be found on Rùm. On the beach we find multiple gemstones. We also find driftwood and some washed-up artifacts – the driest logs we take back to the bothy for tonight's fire.

Millennia of sea violence have carved the west coast of Rùm into many inlets and sea caves. As avid cavers, Liam and I are all too eager to find shelter in the dark holes. Some caves come to a dead-end, complete with animal excrements, others cut straight through the sea until we reach the next cove. One tunnel climbs out to a striking arch, carved perfectly from a sandstone rock. Later we see a flock of feral goats on the sloping foot of a cliff. On the way back over the high coastal cliffs we are carried by the wind. Red deer make their way to Orval’s snow-clad hoof. There's a whispering sound, and shadows on the moonlit moors.

Next to the guest book of Guirdil Bothy, there’s a copy of the 18th century poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner by Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Once again this is a seaman's tale, this one on an eerie voyage home from the South Pole. His murder of an albatross leads to all sorts of supernatural terrors for his crew. Ghastly illustrations narrate the story.

In the freezing cold we plunge into Guirdil river. Then a sprint through the dark, back to the bothy. Steam evaporates from our naked skin. The fire feels even warmer now, and even more welcome.

It raised my hair, it fanned my cheek

Like a meadow-gale of spring—

It mingled strangely with my fears,

Yet it felt like a welcoming.

That night spirits rage the ocean, and an albatross flies over.

Guirdil was a cold and barren place, no trace of human life for miles around. Confined by the bay, its desolateness started to get to me. I could feel it pressing down on my mental state, which, at the time, wasn't in a great place to begin with. After two nights with no escaping from the rain and wind, we decided we had to get moving, change atmospheres.

Kilmory

A throbbing headache and a lot of faff mean it's two o'clock before we depart from Guirdil Bay, when the sky is already darkening. The temperature has risen and the hills have lost most of their snow cover. Meanwhile, Glen Shellesder Burn has expanded a great deal. The rocks we crossed over on the way here, have been washed away by the rainfall and snow melt. We follow the river upstream in hopes of finding a more suitable crossing place. But the river only grows wider, and deeper. In the end we have to make do with one large boulder in the middle of the river. Stepping to it is easy, but from there it's a big jump to the other shore. Liam narrowly makes it across, but my legs aren't that long. With all my might I hurl myself across the river. My body lands in the course reed, but my legs are almost swept away by the current. Just in time, Liam pulls me to the shore. I get away with only wet feet. Glen Shellesder is now a proper swamp, so there was no escaping those anyways. For miles we tramp through the mud till we rejoin the vehicle track between Kinloch and Kilmory. We turn left, towards Kilmory Bay. It is dark, but the coast glistens in the moonlight.

Kilmory is the location of the world's longest-running study of a wild population of deer. Over the past 50 years, 250 individual red deer have been followed over the course of their lives, and world-first discoveries have been made about their behaviour driven by evolutionary forces and climate change. Does, for instance, give birth earlier in the year as the climate warms. And this change has been going on since 1980.

The lights of the research building are off; the deer are resting after the autumn rut and the researchers are hibernating too.

We pitch our tent in the shelter of a hillock and eat a makeshift pot of noodles. For a moment the sky clears and I roam over the damp grass, under the spell of the stars. It's a beautiful last night on Rùm.

We are crouched in the grass and look out over the beach, hidden between rocks so as not to disturb the deer. They're strolling over the rippled sand, the herd that comes here generation after generation. They aren't timid; this morning I ran into several does near our campsite. It's a turbulent morning; splashes and gusts shake me up. Low mist hangs in the bay, constantly changing shape, through it a soft morning light, unexpectedly beautiful.

We walk back to Kinloch so we can take the ferry back to the mainland later today. In the couple days we were here, the island has gone through a metamorphosis. Barkeval is naked and grey underneath its winter coat.

A man in an orange ATV passes by us. He's the first person we see in days. He drives on to Kilmory. Fifteen minutrs later he comes back and stops next to us.

‘On your way to the ferry?’

We nod.

‘It isn’t running till Thursday.’

We haven’t had signal for days and have no idea of the storm raging at sea. Even in Kilmory Bay it is now so strong the man can’t carry out his fieldwork.

Traffic has been halted for two days. The islanders aren’t happy about that. Today is December 20th; Thursday is their – and our – last chance to get home before Christmas.

‘Don’t worry, I’ll get us out of here on Thursday, even if I have to do it myself.’

Rùm isn’t ready to let us go. We don’t know where we’re going, but we’ve run out of food, so we first have to go to Kinloch, where the only grocery store on the island is.

Kinloch

‘Surely you aren’t going camping in this weather?’ The shop owner looks at us in disbelief.

When one of 30 inhabitants of a Scottish island tells you this, you know you’re doing something crazy.

‘I was actually thinking about camping in Harris,’ Liam says later, when we walk to the BBQ hut on the other side of the village. Jinty has offered us her cabin on the lochside for the price of two packs of charcoal to light a fire with. In summer she rents out the hut to tourists on the island, but now it’s been empty for months.

It’s a gift, this cosy shelter, after three wet days on the coast. The wooden hut is soon filled with a heady smoke. We spend the winter solstice with our feet up, playing cards and drinking beer. Outside a cold wind blows, but we are warm inside, cuddled up by the barbeque.

And the coming wind did roar more loud,

And the sails did sigh like sedge,

And the rain poured down from one black cloud;

The Moon was at its edge.

These are my last days in Scotland before I return to the Netherlands for I don't know how long. This knowledge weighs heavily on my shoulders. How can I leave this land behind, the wild soil and the humming waves that hold my heart?

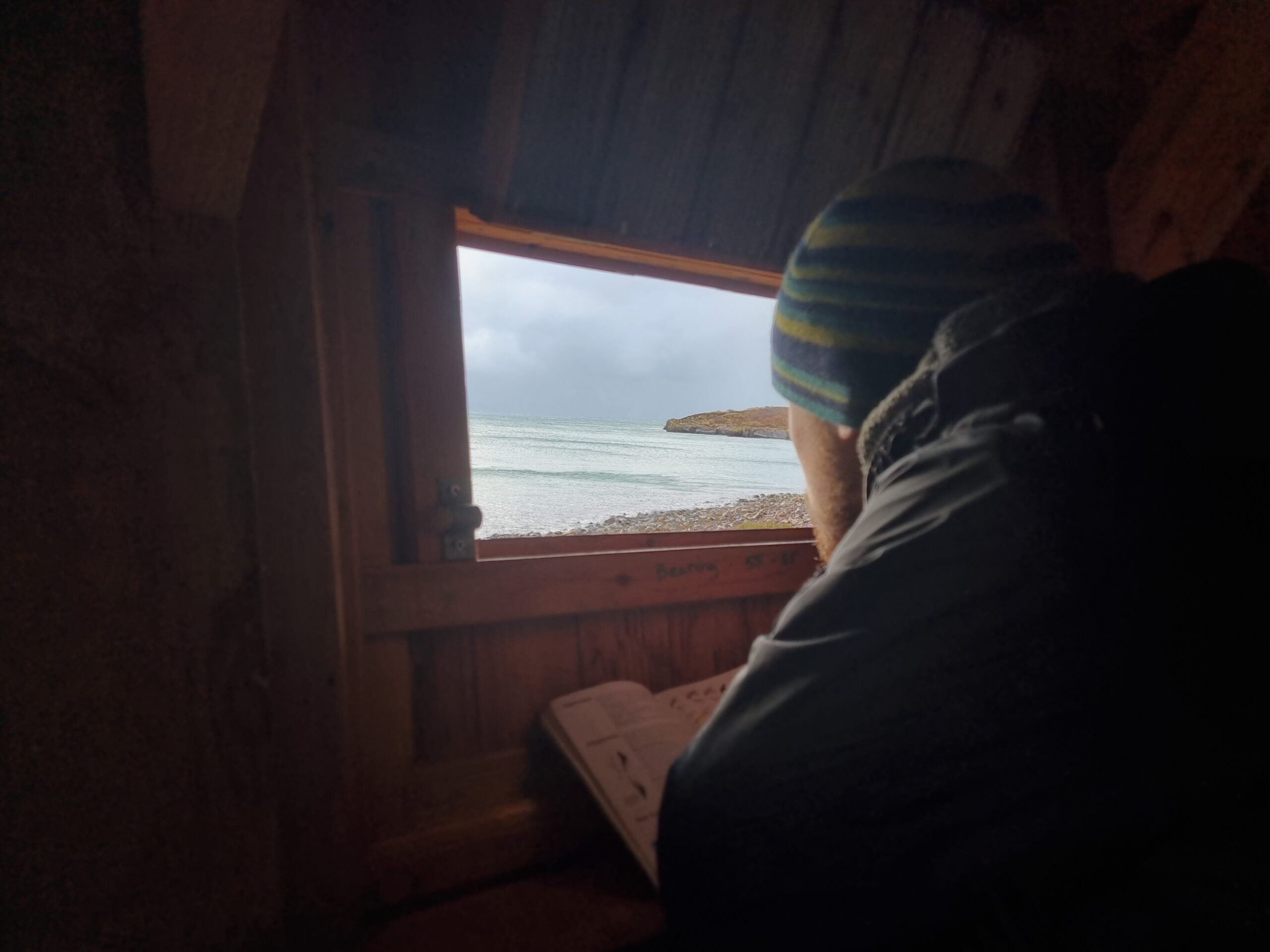

Night reaches its apex, and I want to hibernate, too. Let the darkness around me into my heart. Liam, on the other hand, is restless, finds refuge on the trails and the shore. I stay inside, but not for long; when Liam finds an otter hide, I know I need to hatch from my coccoon, to see it too.

The hide is on the edge of the forest, looking out beautifully over Loch Scresort. In the logbook sightings have been noted of seals, otters, whales even. With help of wildlife guides we spot seals and lots of waders and water birds, but no otters.

We follow the coastline east, in search of a set of caves and a standing stone that are marked on our map. First over old tracks, through lovely woodland with overgrown ruins, but later on the land is reclaimed entirely by nature. We find the remains of a settlement, Port na Caranean, abandoned in the 19th century. The last dwellers here are believed to be crofters evicted from Skye. It's a remarkable place, as close to the sea as you can get; there’s nothing here except the Skye Cuillin on the horizon. Maybe the crofters picked this strip of land, however barren, for that reason; so their home would always remain in sight.

We climb up and down over rocky coves and pebble beaches, through peat bog and tall grass. The peaks of Hallival (722 m) and Askival (812 m) tower above us, shimmering with the last shreds of snow. The caves are further still, beyond a couple rivers along the coastal cliffs. But the sun is setting, and navigating back in the dark will be even harder. So we have to turn back around. And this isn’t without reason; come twilight we nearly get trapped in a coppiced woodland.

For a hamlet with but 30 people, there's quite a lot to see in Kinloch. Of course there’s the misplaced Edwardian castle, that has been vacant for years. But there’s also a village hall, a visitor centre and a craft shop, and their doors are always open. Every morning there's warm coffee at the village shop. Even now, at the dead of winter, I feel a sense of community here. It's a simple life, that follows the push and pull of the tides. It ain't easy; it's hard work keeping the shop and school running. Life here is subject to the storms at sea; they determine the supply of goods and the connection to the rest of the world. Sometimes people need to depend on themselves, and each other, for days. Now is one of those times.

On Thursday morning the sun finally makes an appearance: Rùm's last attempt to keep us here. But sun means escape too. The islanders flock to the ferry terminal, and we go with them. Excitement is palpable in the air. There's only a few people who remain on the island over the holidays, whose deepest roots lie here.

I didn't know it at the time, but now I see the whirlwind I went through that midwinter on Rùm for what it was: necessary. Cause it isn't only bliss that we ought to feel in the wilderness, it's everything all at once, from fear to awe to pride, from great joy to desperation, and that's the beauty of it. They're all part of our nature. And they all need to be felt. To feel the darkness of this place meant I could once again feel wonder; for the shearwaters and the ancient crofts, for the screaming mountains and the deer rut. Of course…yes of course my mind wanders back here over and over, to the place where I found comfort in a small BBQ hut amidst the wailing of winter.

Leave a Reply