All around me is water. I am standing in the middle of a wild river, while rain pours down on me. All my muscles contract to keep in balance. One misstep, and the river takes me. Laughing, I wonder how it has come to this again. That is Scotland; she draws you to her against all reason. In the biting wind, while the elements rage past me, that is where I am most alive.

Nov 17, 2022

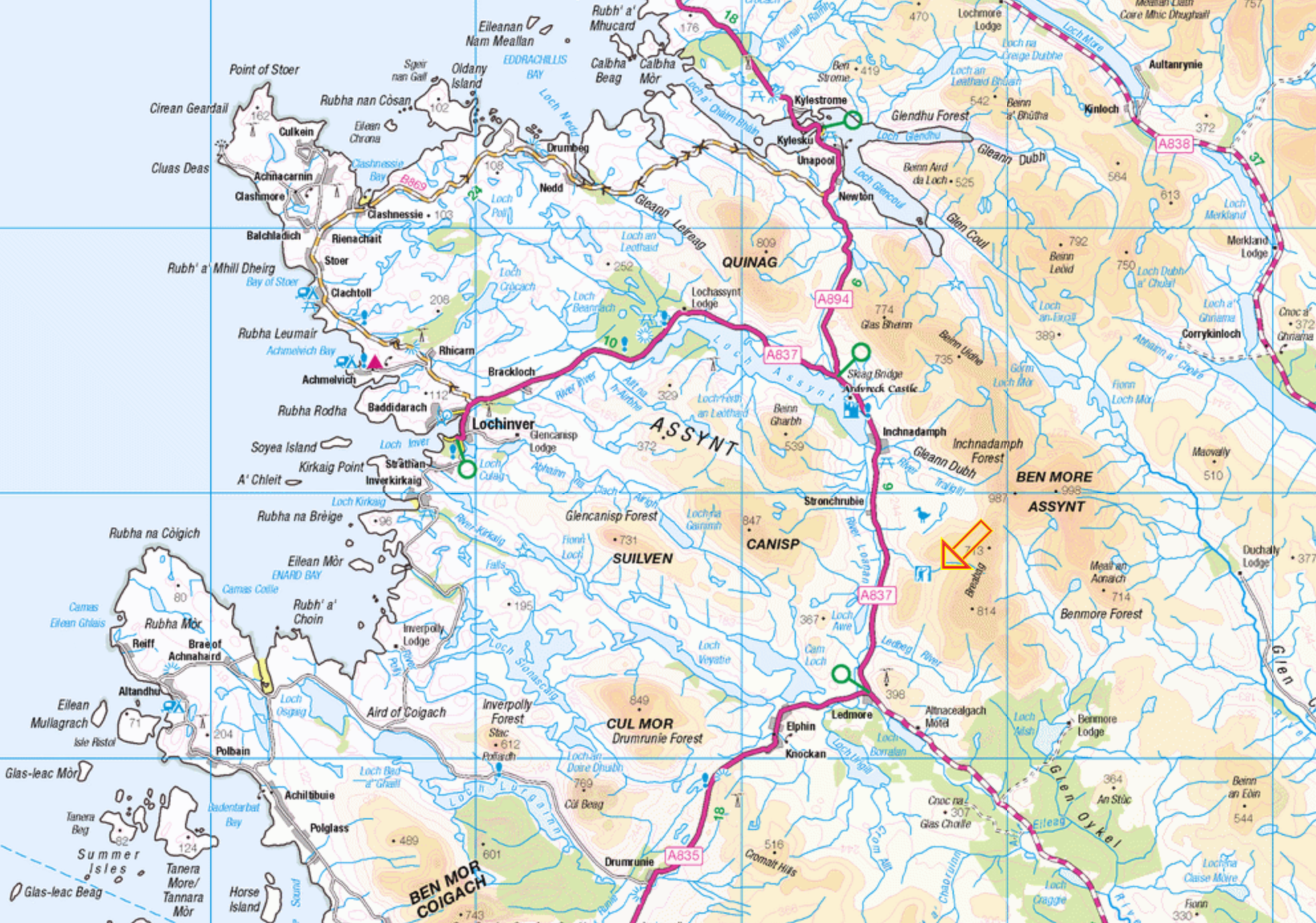

On a stormy Thursday evening somewhere in November, a rattling Ford Transit leaves the bustle of Glasgow. Its destination: Assynt, far away in the high north of Scotland. With its fabulous hills, emerging from empty land in solitude, this place has always been the stuff of legends.

It is late when Liam and I finally hit the road and our destination is far out of reach today. But it doesn’t matter: we are on our way, on our first big adventure together! The air between us bursts with excitement. What we don’t know then, but do secretly dream, is that this will at once be our most epic adventure.

We swing until deep in the night on electronical Gaelic music and stop in a dark parking lot just outside Inverness. Police cars by the roadside cast an eerie, purple glow through the trees. In the morning we wake by the clatter of raindrops on the skylight. An omen of the torrent that is to come that day.

We have a 2,5 hour drive ahead of us today, with a stopover in Inverness where we stock up for the weekend. After this we leave civilization behind. As we get further north, I notice how the landscape widens. It’s as if every hill tries to take up as much space as possible to enforce its power. It works: the Highlands hold me in their grip.

We pass by Ullapool, the last village of any significance, and Elphin, nothing more than a couple houses among the hills – one of them the hut of the Grampian Speleological Group.

Caving or potholing is the sport that deals with exploring wild cave systems. This involves scrambling over rocks, abseiling into deep pits, crawling through mud, and squeezing through tight spaces. What you get in return are muscle pain and a lot of bruises, but also dazzling passages decorated with stalactites and stalagmites, winding canyons and bellowing cascades. It’s a niche sport; in the whole of Scotland maybe a few hundred people are actively involved in caving. Most of them go down to Yorkshire Dales in England, where the most extensive subterranean system of Britain is located. In Scotland, only the caves in Assynt are visited with any regularity. Just a handful of people have set eyes upon the other caves.

Cavers are a quaint group of people – you’ve gotta be a little mad to go down a pitch-black hole in the ground voluntarily – and one that I felt immediately drawn to for exactly that reason.

Liam often comes to Elphin to go caving and he assures me that it’s the best caving hut in the country; in the morning you have breakfast in the conservatory that looks out over the peaks of Cùl Beag, Cùl Mòr and Suilven. Today this view has to remain due; the hills are covered in thick clouds.

Suilven. The hill that first stole my heart three years ago. She demands all eyes in her vicinity to look at her, with her dome emerging out of nothing like a primal force, mighty and lonesome. I had longed to catch sight of her again, but I have to be patient: she does not reveal herself easily.

Allt nan Uamh glen

It is tempting to seek shelter from the rain between the cozy walls of the hut in Elphin, but on a stormy day like this we have no business aboveground. So we continue driving, till we reach a car park at the head of a wild glen, where an underground maze lies hidden along the river Allt nan Uamh. In summer the glen is popular with walkers visiting the Bone Caves, where the remnants of a reindeer, lynx, bear and even a polar bear have been found. But on a turbulent November afternoon it’s empty here, its coffee stall deserted.

Liam and I crawl into the back of the van for lunch, doors closed for shelter. Even underneath my blanket I can feel the bitter wind. It’s important we fill our bellies – we can only take some cheese and granola bars underground. As long as possible we postpone the moment where we yield to the elements, that rush through the valley uninvitingly.

Reluctantly I lift myself into my caving kit. Thermo, fleece, undersuit, oversuit. Knee pads on my knees, helmet on my head, feet into my wellies. In a waterproof rucksack we bring a route description, spare torch, emergency signal, first aid kit and water bottles.

It’s already getting dark when we finally set off, while the clock has not yet struck four. The fierce clouds aren’t lying: the glen is flooded. Liam points to a waterfall that crashes down the rocks violently. Last year, the cavers bathed in the pool underneath; the water stood almost still. Now a river rushes through the streambed at full speed.

We wrestle through the bush along the riverbed, deeper into the valley. Above us the Bone Caves gape at us like black holes. They look impressive, carved out of the limestone cliff of Beinn an Fhurain, but for serious cavers these shallow caves offer little challenge. We are seeking a cave further up the glen, located along the riverside, therefore bearing the name Allt nan Uamh Stream Cave shortened as Anus among cavers.

We pass by a tiny cave that sits in the streambed. The spate has wiped away its entrance. We are starting to doubt that we’ll be able to enter Anus in this state.

Before we find out, we first need to find her. And that is no easy task in the sinister state of the landscape. We scramble up and down the slope that climbs out above the river, searching with our torches for an opening in the rock face. We come to the conclusion that Anus lies in a notch of a small cliff, barred by the fast-flowing river.

It’s impossible to reach the cliff face from our shore. If we want to get to this cave, we will have to go through the river. But it is relentless, and we don’t stand a chance against the current. Our only option is to cross the river twice where the flow is most still. The other option – to call it a day and return to the van – is one we refuse to say.

Liam examines the riverbank for the most suitable spot to cross the stream. Several times he struggles over slippery boulders, with no luck. I see the forces that wield over him, the tremble in his usually steady body. I am mad to think I’ll keep upright here.

Liam succeeds a little downstream. He disappears from view when he makes the second crossing. A moment later he reappears. He shouts at me, but the river smothers the sound. Once more he makes his way through the river, back to me.

‘The cave is free!’ he gleams. ‘The current is strong, but not impossible.’

I am not so sure about that. My mind wanders off to the last river I crossed, on a trek in Iceland a year and a half ago. I was prepared then, wearing water shoes and holding hiking poles to steady myself with. And yet my heart was racing when the icy water clasped my legs. I’ll take a mountain to climb over anytime; on the bedrock I am sure, where the soles of my shoes fixate in the earth, but in a river I lose control. The rocks slip away under my feet and a single jerk of the water can sweep me away.

My gaze drifts into the hills, to the Bone Caves which we have left behind us. Suddenly they look a lot more appealing. But I had reached the other side before, why not this time? I am wearing a helmet, and if I slip the river cannot take me far – it is too shallow. At most I’ll get wet and scratched, but this I am already. It’s the tickle of that possibility that gets the upper hand, the question of what lies hidden there in the darkness.

So here I am again, in the dark. Not surrounded by clouds this time, but by a bellowing river. I have no hiking poles, but I do have Liam’s arm as my rock in the surf.

‘Take your time,’ he says. ‘Be certain of every step you take.’

The water rises to my thighs and rages violently past my body. Every time I lift my foot, I almost lose balance. I feel the power the water has over me. But I stand ground, from the sheer will to set eyes on that mythical cave. And each careful step forward slowly leads me across.

Allt nan Uamh Stream Cave

I shine my torch across the river. There she is: Anus, a gaping hole in the rocks, just above the river. The second crossing is easier and I reach the shore without struggle. A dam has been built in front of the cave to keep the water out, but it comes alarmingly close.

We don’t know how fast the water level rises, if the cave has ever flooded and how dangerous this would be. I peek inside. The entrance is a two meter climb down into a chamber of standing height. The floor of the pit is dry apart from a small puddle. The chamber immediately narrows into a tube through which you need to lower yourself feet first into a lower chamber. Underneath an arch the room opens into Assembly Hall, and from here the rest of the cave.

It’s reassuring that the cave mainly drops down in the first section, with enough channels through which water can drain. Should water flow down the cave, in all likelihood it will not flood completely. And should it prove too difficult to make our way back against the current, there will be safe, higher spots deeper in the cave where we can wait till the water level has lowered, or – worst case – until help arrives.

Of course, this is a mere prediction, based on the couple times Liam has been down Anus, in very different conditions.

I am standing in a hole in the ground, above me a river roars past. Oh, the madness of it all. And yet, and yet… Anus is there for the taking, and I cannot help but want to see her.

We settle for a quick trip down the cave, all too aware of the risk we’re taking. In a few hours we’ll be back on the surface, or so is the plan. In a rush we go underground then, the river Allt nan Uamh hanging over our heads like the sword of Damocles.

Liam’s phone is soaked after the first minutes inside despite its waterproof case – a lesson that every caver who dares bring his phone learns – and he has to leave it at the entrance. And so it is that Anus remains a mystery to the outside.

The first leg is a lot of crawling. Low tunnels that you can only get through lying flat on your belly. One of them is filled with water. With my head turned sideway so as not to submerge, I wriggle my way through, as water seeps into my sleeves. It’s hard to imagine how much effort even a short crawl takes. You rely entirely on your hips and elbows to move forward, your feet have no ground to push against, and your knees do nothing but bruise.

Eventually, the cave opens up and we can stay upright as we proceed along Sotanito Passage. We traverse a couple of deep pits, that connect to an alternative route down along the stream. When I see the depth beneath me, for a moment I forget to breathe.

Anus is a raw, gritty cave. She isn’t smoothed by erosion like the caves I’ve seen in England, but is rougher in nature, bearing gravel, loose rocks, and rugged crags. It’s not a cave I’d call beautiful at first sight. But if you manage to see through her harsh appearance, you’ll find there is so much beauty even in this place.

It’s a labyrinth with an infinite number of routes, most of them ending in a choke, but some lead to a sump, or possibly another cave. Other passages loop back to an earlier junction. You can get lost in it for as long as you want. All passages eventually reach the main streamway, that forms the underground section of the river Allt nan Uamh. An abundance of water flows through the streambed, a reflection of the flood up in the glen.

We keep well above the river and follow it upstream. A thundering sound grows louder and louder, penetrating every fiber of the cave, as a constant threat in the distance. It’s coming from the Thunderghast Falls, the waterfall that we’re looking for. She seems to be around every next corner, that’s how much noise she makes. But the waterfall is well-hidden. We have to clamber up a muddy, slippery tube to reach the viewpoint. It ends in a small platform, enclosed by walls on two sides, which drops down abruptly. It’s a tiny space and we huddle together lying on our bellies, to peer over the edge.

An enormous volume of water cascades down a glistening precipice. It’s astounding how much noise clashing elements can produce. The waterfall is only meters beneath the earth’s surface. Just above us is the equally thunderous Allt nan Uamh, which we stood next to not long ago. But down here she might as well have not existed. There’s no knowledge of the storm that rages in the open air, of the sun that sets and rises, of the life hatching in every corner. A cave is a world of its own, and one where time is nonexistent. Meanwhile we’ve been inside for over an hour, and we need to head back soon. Because outside Allt nan Uamh keeps on flowing, and she might be flooding the cave at this moment.

Downstream, Anus cuts much deeper into the earth, through phreatic tunnels and vadose canyons. We’ll save them for next time. We retrace our steps, pause only to squeeze one last time into a vertical cleft in the rocks, where we gobble up some Babybel cheese. We are hugged by the tight walls around us. There’s only the sound of running water, now a comforting swell in the distance.

One of the most special things about caving is the complete absence of light. Turn off your torch and you’ll be surrounded by absolute darkness. I don’t think you can ever experience this in the outside world, where your eyes adjust to the smallest amounts of light emitted by the stars and reflected by the moon, even in the deepest wilderness. But underneath the surface there’s not a single source of light. You can move your hands in front of your face, eyes wide open, and you won't see a thing. Oddly enough, it sometimes seems as though there's a flicker in the corner of your eye, but this is just your brain projecting what it expects to see, like a phantom, not used to the nothingness.

We sit like this for a couple minutes, enjoying the lack of stimuli. We feel each other’s presence without the need of our eyes and ears, and after a while we find each other, purely by instinct.

In one go we rush back, this time familiar with all the obstacles. You can feel it when you near the surface. There’s a crispiness in the air and the earthly smell of moss. Sensations that you wouldn’t notice aboveground, because your body is so used to it. But here they’re a sign of life. From inside it’s hard to make out the arch that gives way to the exit - that’s how deceptive perspective can be. We let our senses guide us to the fresh air.

I hold my breath when I stick my head through the tube and see the dark skies. The exit is free! Elated we climb outside. The outside air wakes me, as though I’ve been submerged for hours and can now gasp for air again.

The dam has withstood the tide, but not only that; the river has shrunk. In the few hours we were underground, the water level has lowered at least ten centimeters. It has stopped pouring and suddenly the glen has a calmness to it. It is shocking how fast the landscape has changed – for all we know it could have been the other way around. Maybe we assessed the risks correctly, but in all honesty it was pure luck. Anus may never have flooded before, as we discover later; these days Scottish weather is subjected to such extremes that nothing is certain.

We stand to see another day, one in which we’ll encounter many more extremes – we just cannot seem to escape them.

Many thanks to the Council of Northern Cavings Clubs and Grampian Speological Group; their detailed cave description made this trip and the writing of this blog possible.

Leave a Reply