Everyone who knows me a little, will know by now that Assynt is my favourite place in Scotland, maybe even in the world. When people ask me why, I sometimes struggle to put this into words. But this summer has reminded me of what it is: evenings in the conservatory, the endless sun, the windswept moors, hills that hide their shape, hills with fossiled scales. Not even the midges can take my joy away, although they give it a good go.

Joevie and I say goodbye in Ullapool, where we’ve been given a ride all the way from Corrie Hallie by two kind Scotsmen, psychiatrist Tom and his partner Conor. Joevie is returning to Glasgow, I’ll carry on to Elphin. But not before we’ve eaten a divine wood-fired pizza from Oak & Grain. Well-deserved after our hardships in the Fisherfields.

In Assynt I am meeting friends from the Glasgow University Caving Association for a weekend full of caving fun. The caving hut in Elphin is our beloved base. Nothing beats sitting in the conservatory on a sunny morning, excited for the day to come, or late at night, with that long last trace of light in the sky.

And the hills of Assynt, always there, in the corner of your eye.

Claonaite

Assynt is the caving mecca of Scotland. The most important caves for cavers are in the Allt nan Uam glen, just to the north of Elphin. On previous expeditions in Assynt I visited Allt nan Uamh Stream Cave and Rana Hole, but one cave in the valley remains undefeated: Claonaite.

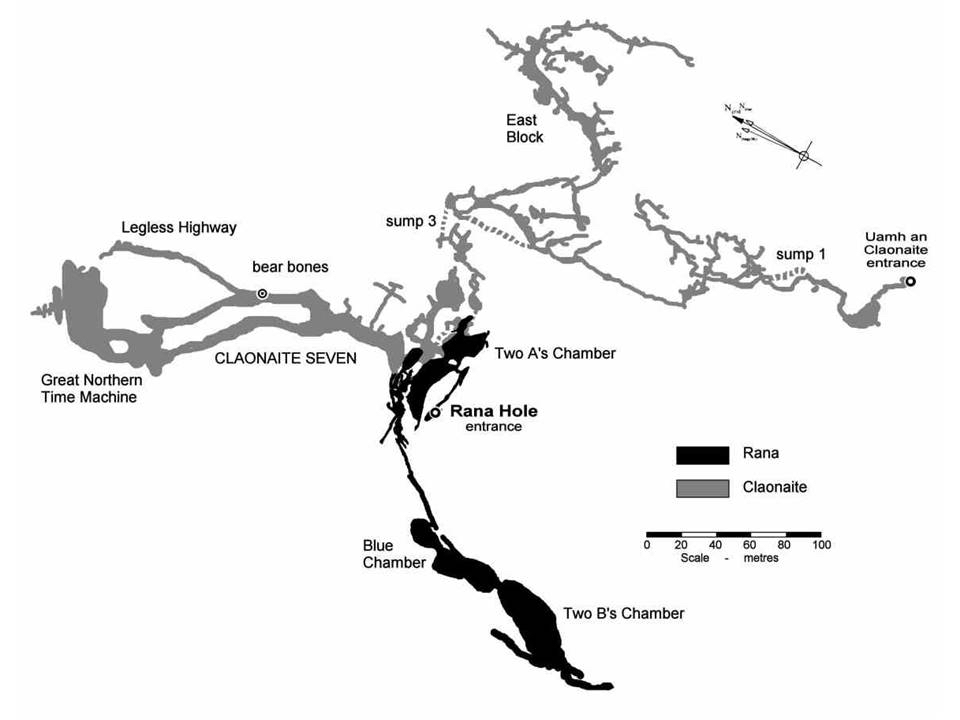

Close to 3,5 kms long, Uamh an Claonaite, ‘Cave of the Sloping Rock’, is the longest cave that’s been excavated in Scotland. Only a small part of the cave is accessible from Claonaite’s entrance; the cave has around seven so-called sumps, passages that are flooded and can only be traversed by diving – a whole other discipline of caving that is reserved only for the bravest amongst cavers.

Two of the sumps can be bypassed but after 750 meters sump 3 blocks access to the rest of the cave. 750 meters isn’t a challenging distance for a cave, and yet no one in my group has ever reached the far end of Claonaite; this is because the caves of Assynt are extremely subject to weather changes, and Claonaite in particular.

On my last attempt I didn’t get past the first 20 meters, where a cleft had transformed into a huge waterfall by the heavy rain. We tried descending past the waterfall, but even the strongest in our group struggled to climb back up it. We had to abort mission.

It’s early August now and the water level in Assynt is lower than I’ve ever seen it. The river Allt nan Uamh, which I fought a raging battle with two years ago, is all dried up. Big boulders fill the river bed. The conditions are perfect for a rematch in Claonaite.

Last time I was here, winter had drained all colour from the landscape. Through bare branches that swayed in the wind, I could look out far over the barren brown hills. Now, the glen is overgrown with green, the ferns so thick I can hardly see the valley. It seems an entirely different place, such is the change of the seasons.

To reach Claonaite and Rana Hole (both are part of the same cave system), you follow a tributary of the Allt nan Uamh up a gully east of Creag nan Uamh, the rock face that harbours the Bone Caves. These small caves are known for the remnants that were discovered here of reindeer, lynx and polar bears that once roamed this place. The glen flattens out to an unmarkable moorland until a sudden depression in the landscape. And there is Claonaite, a gaping hole beneath a limestone cliff.

We do not linger – at the height of the midge season, the underground is a lot more pleasant than the tall heath. One by one we lower our bodies into the earth.

There’s five of us today, and it’s Liv’s first time going underground. Through her eyes I get to experience that first time in a cave all over again.

‘Were you scared the first time you went into a cave?’ Liv asks me as we climb through a narrow canyon.

I have to think about that for a moment. ‘Not really. But I didn’t know what I needed to be scared of.’

I had never read horror stories, or saw videos of cavers getting stuck down a cave. I went in blank. For Liv it’s different. For years she’s heard all of Daniel’s stories – the great as well as the gruesome. Those take on a life of their own in your head. No wonder that she’s refused to do it up until today. Somehow Daniel has got her to come along this time. The grin on Liv’s face tells me she’s not regretting it.

It certainly is a full emersion in the world of caving. That cliff that brought a premature end to my last trip, is merely slippery this time, but still it’s a 4-meter drop to a pool that I wouldn’t wish to fall into.

We give each other a hand or a direction. That’s the beauty of caving: you do it together. In a cave, each person has their own strength: one is strong and helps the others up, another is small and can check out tight spaces, yet another knows all there is to know about knots.

Claonaite is a very entertaining cave, a good mix of crawling and climbing, of goofing around and getting wet, of good exercise and then resting underneath calcite decorations. It’s also a very wet cave. Sometimes the water rises up onto my chest. And of course that comes with a perfectly nasty wet crawl. Elbows, chest, face – no body part is spared. There’s no doubt that last year we'd have needed to swim through.

Compared to Allt nan Uamh Stream Cave, which has a complex network of routes, navigating through Claonaite is relatively easy: we keep to the river and follow it downstream. There’s one spot where we aren’t sure which way to go – to the right I check out a passage from a raised platform that appears to choke, but to the left the route through the river also looks like a sump. Patrick volunteers to take a better look at the right passage. Wiggling feet and a muffled voice tell us it only grows tighter. He emerges from the hole looking like a mud monster.

My favourite part of Claonaite is the long, slanted rift we move through sideways. Had I brought a camera, it’d have made for a spectacular picture. We climb down inclined slopes and cascades (named the Watershoots), and before I know it we’ve reached sump 3. A blue pool stretches out far beyond the scope of our light. Was that it? It’s not a thought I often have in a cave.

Beyond sump 3 there is much more of note – ancient bones, mud formations and as centerpiece the Great Northern Time Machine: a giant chamber – at 30m high and 70m tall the largest on the Scottish mainland. Rana Hole was excavated to allow access to the Great Northern Time Machine without the need of diving. This way, two separate caving routes were created in the same cave system: a horizontal one and a vertical one that needs single rope technique (SRT).

For a small group Claonaite has the perfect length to entertain you without being too exhausting. We retrace our steps with the same enthusiasm and energy, now with the promise of beer and a sun still shining on the surface.

On the way down we had to take care (although Daisy saved time by simply sliding down), up the hand- and footholds are easier to distinguish. I wedge my body between the walls. Sometimes I think I lose control – a shiver through my spine. In many ways it’s a mental game, the fear of falling. Keep yourself calm, and you’ll retrieve your balance.

The biggest challenge is that last cliff, 4 meters straight up. While I lunge myself from one wall to the other, Daisy finds an alternative route up the platform. That’s the fun thing about caving: there are no rules, you are free to explore, find your own way.

On the way back through the Allt nan Uamh glen we check out the Bone Caves. In the middle of summer it’s teeming with people. In the karst regions of England, especially Yorkshire Dales, cavers are a common sight. In Assynt we look like aliens next to the tourists, with our red-blue suits and helmets, waddling over the heath. It isn’t too far off from how we are feeling, seeing daylight after hours underneath the earth.

Cnoc nan Uamh

This weekend we share the hut in Elphin with a family from Southern England. Andy and Kirsty are two cavers who have been taking their kids to the caves of England and Wales from a young age. This summer is their first time caving in Scotland.

Most British cavers get into caving in their student years through one of the university caving clubs. Skills are passed down from generation to generation of students, but rarely from parent to child.

Cavers graduate, get a grown-up job and caving becomes a nostalgic memory from their youth. But now and then, two cavers find each other (more often than you think) and sometimes they stay together. And then caves become your summers, splashing, scrambling, rolling in the mud with your children.

What a rich world that Abi and Hedley grow up in. I’ve not met many children that have such an unfiltered presence in a group of strange adults. There is a confidence in their speech and a freedom in their manners that I think can only be the result of their adventurous upbringing. Caves are a natural playground, and fuel for the imagination.

Evenings in the caving hut sometimes involve a cup of tea and good conversation, browsing through caving journals by candelight, reminiscing and plotting the next adventure. And sometimes they’re laughing and screaming until the early hours of the morning. Saturday is one of those nights: we play games for hours, each next one crazier than the last. The most legendary caving game is the ‘squeeze machine’, a wooden device that you need to squeeze through, while the gap grows increasingly narrow. We didn’t bring it this time, so we have to make do with objects in the room. There’s plenty of them: we climb around a table top without touching the ground, and catch objects from the ground with our teeth – the only rule: hands on your back. Many years ago Andy and Kirsty played the very same games – nothing much changes in the caving world.

We are most occupied with the sling game – standing on an upside down pan, two people have to free themselves from a sling without falling off the pan. Piper, our yoga master, and I make a good effort, but Andy and Abi are by far the best team, mostly thanks to Abi’s small flexible body.

On Sunday, Piper (yesterday she and Amber got defeated in Rana by midges and bad slings) and I head out on our own. In the caving book of Assynt a photo of ‘the Grotto’, a beautiful chamber with calcite formations, sparks our curiosity.

The Grotto can be found in Cnoc nan Uamh, or ‘Cnockers’, a cave system in the Traligill glen, further north near Inchnadamph. The English family visited it yesterday. Excitedly, Hedley tells us how they found the chamber, it was a whole quest!

The caves of Traligill may be shallower than those of Allt nan Uamh (and thus often skipped in favor of their southern neighbours), they are no less beautiful. Andy says he’s never seen anything like ‘the Waterslide’.

It’s Piper’s and my first time leading in a cave. Soon enough we realise cave navigation is even harder than it seems.

The first step is finding the cave. Kirsty’s instructions are clear: 400 meters after the last house, the cave entrance becomes clearly visible in the hillock before you. But Traligill glen is rich in limestone and everywhere around us there are black holes in the landscape, trying to confuse us.

The sign that says ‘cave’ is not to be missed though, and it isn’t long until we see the hill of our picture, Cnoc nan Uamh, ‘Hill of Caves’. There are three entrances, Uamh an Tartair, that gives way to the main section of the cave, Uamh an Uisge, by the Waterslide, and a nameless pothole on the hilltop.

The Waterslide is every bit as impressive as Andy made it out to be. A cacophony of water plunges down a wide thrust plane, perpetually. Where all that water's coming from is a mystery to me. And to think that we are in the middle of a drought!

The easiest way to reach the Grotto is through Uamh an Tartair, so this is where we enter the cave first. We duck under a low arch and drop down a slit into Stream Chamber, the main passage through which the river flows. From here we are looking for a muddy crawl on our right side. We try several openings, but they all come to a dead end.

A second attempt from Uamh an Uisge – by following the river upstream we hope to find the passage to the Grotto. The streamway itself is a spectacle in its own right. We pass by a waterfall with light falling through from the pothole, a magical sight, we wade through a hip-deep canyon and climb straight up a cascade above a deep pool. After a narrow crack the cave opens up into a chamber, but I recognise the straws on the ceiling. We’re back in Stream Chamber.

From left to right: Uamh an Uisge with the Waterslide, Uamh an Tartair and the Pothole Entrance (Videos: Piper Cusmano)

Still no Grotto, and time is running out – we have a 5 hour drive ahead of us across Scotland.

Apart from the muddy passage there’s another route to the Grotto, by following the river upstream. This comes with a series of ducks and is only possible in low tide.

It’s our last attempt. We wade through the stream until an arch blocks passage. Shining our torches underneath, we can just about see past it. Two short ducks and the cave opens up again. Who knows what beauty lies behind it.

The stream seems higher than Andy and Kirsty described it yesterday. There’s been heavy rainfall last night and this morning, so perhaps the water level has risen already.

Piper draws the line here, but my curiosity gets the best of me. I decide to check the other side out briefly, while Piper waits in Stream Chamber.

I’m only under for seconds, much briefer than when I swim in the sea, but the limited visibility make it feel a lot more scary. I duck under till a split in the roof, and another time, first against the rocks with my big helmet, then underneath them.

I climb onto the shore and am standing in a round chamber that’s called Pool Chamber. I follow the sound of running water to a chamber with a small but powerful waterfall. It isn’t the Grotto.

There’s multiple ways to go on from Pool Chamber. One of them will lead to the Grotto, but it will take time to figure out which. This isn’t something I should try on my own. So I go back to the duck. I shout Piper’s name but she doesn’t hear me. For a moment I panick – is this the right way back? I go back to Pool Chamber and look around for other routes but I’m sure this is the way I came. The second time at the duck Piper does hear me. Relieved I duck back under and am reunited with Piper.

It’s an important lesson for the future: clear rules are crucial, no matter how briefly you separate – how far are you gonna go, where does the other person wait? It’s too easy to get lost in a cave.

We call it a day. The Grotto does not wish to be found today. But we can’t leave without going down the slide.

Once again we are so lucky with the weather — had the flow been any stronger, we would've needed a lifeline.

It’s incredibly freeing, sliding down the Waterslide, embraced by the water, screaming away our demons. I've never had such fun in a cave.

That enormous volume of water, that appeared out of nowhere, it disappears just as suddenly, into the black, into clefts between the rocks. The earth is constantly in motion. Even under rock-solid soil.

Piper’s and my adventure ends here. The surface is calling us. We climb back a lighter version of ourselves.

And that’s another wrap in Scotland. One thing I know now, surer than I’ve ever known it. This is where I belong. Between the lonely mountains, in the hollow earth, with my cavers.

Leave a Reply